References

Ali A, Durieux D, Newman D et al (2023) Insights from an expert roundtable discussion: Navigating intermittent catheterisation associated complications. EMJ. 8(3):38-48.

https://doi.org/10.33590/emj/10306793

André AD, Areias B, Teixeira AM, Pinto S, Martins P (2022) Mechanical Behaviour of Human and Porcine Urethra: Experimental Results, Numerical Simulation and Qualitative Analysis. Applied Sciences. 12(21):10842.

https://doi.org/10.3390/app122110842

Auger J, Rihaoui R, François N, Eustache F (2007) Effect of short-term exposure to two hydrophilic-coated and one gel pre-lubricated urinary catheters on sperm vitality, motility and kinematics in vitro. Minerva Urologica e Nefrologica. 59(2):115-124

Burns J, Pollard D, Ali A, McCoy CP, Carson L, Wylie MP (2024) Comparing an integrated amphiphilic surfactant to traditional hydrophilic coatings for the reduction of catheter-associated urethral microtrauma. ACS Omega. 9 (20):22410-22422.

https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.4c02109

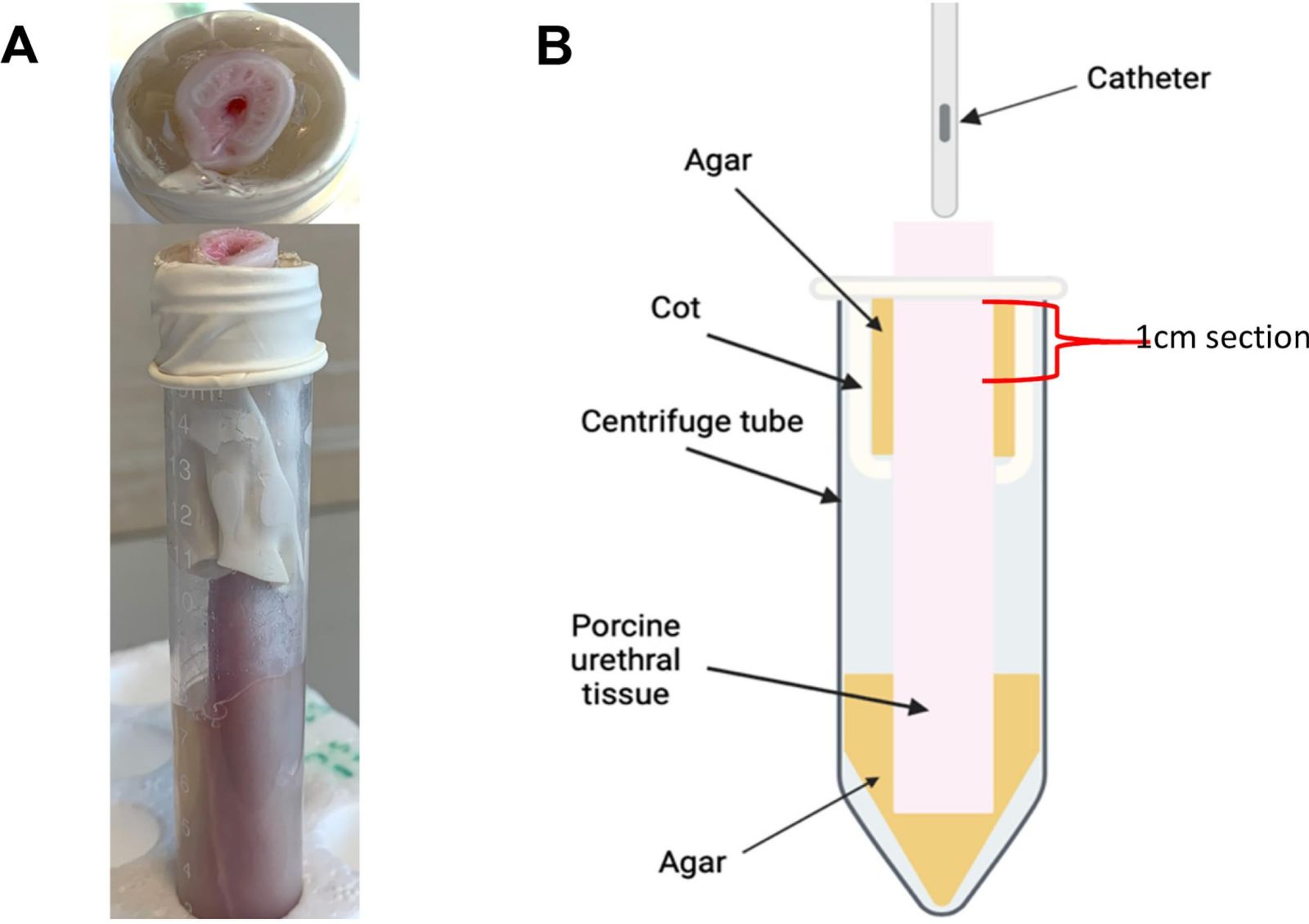

Burns J, Irwin RN, Quinn J et al (2025) An ex vivo porcine urethral model for investigating intermittent catheter-associated urethral microtrauma. Materials Design. 259:114727.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2025.114727

Kato Y, Nagao Y (2012) Effect of polyvinylpyrrolidone on sperm function and early embryonic development following intracytoplasmic sperm injection in human assisted reproduction. Reprod Med Biol. 11:165-176.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12522-012-0126-9

Kazi S, Yang B, Carugo D, Stride E, Lavigne A (2025) A Novel Male Porcine Urethral Ex Vivo Model: Characterisation of Structural and Metabolic Viability. Abstract 657. ICS-EUS, Abu Dhabi.

https://www.ics.org/2025/abstract/657 (accessed 31 October 2025)

Pollard D, Allen D, Irwin NJ, Moore JV, McClelland N, McCoy CP (2022) Evaluation of an Integrated Amphiphilic Surfactant as an Alternative to Traditional Polyvinylpyrrolidone Coatings for Hydrophilic Intermittent Urinary Catheters. Biotribology. 32:100223.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotri.2022.100223

TissueSource (2020) Advancing Urology Research with the Porcine Urinary Tissue Model.

https://tissue-source.com/blog/urology-research/ (accessed 31 October 2025)