References

Andrews HO, Nauth-Misir R, Shah PJ (1998) Iatrogenic hypospadias--a preventable injury? Spinal Cord. 36(3):177-80.

doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100508

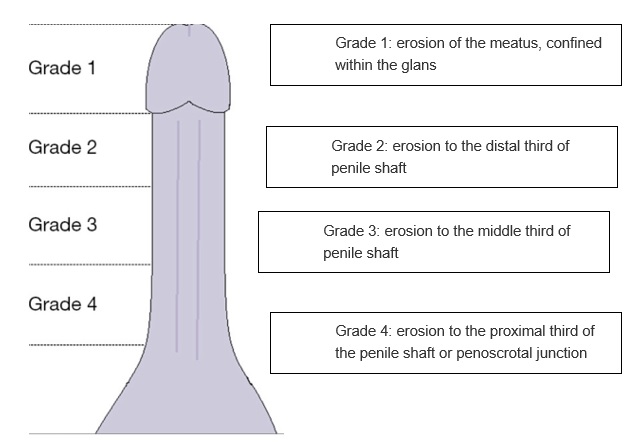

Becker B, Witte M, Gross AJ, Netsch C (2018) Iatrogenic hypospadias classification: A new way to classify hypospadias caused by long-term catheterization. Int J Urol. 25:980-981.

doi: 10.1111/iju.13791

Bhat AL, Bhat M, Khandelwal N et al (2020) Catheter-induced urethral injury and tubularized urethral plate urethroplasty in such iatrogenic hypospadias. Afr J Urol

. 26

:17.

doi: 10.1186/s12301-020-00030-z

Cipa-Tatum J, Kelly-Signs M, Afsari K (2011) Urethral erosion: a case for prevention. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 38(5):581–583.

doi: 10.1097/WON.0b013e31822b3280

Feneley RC, Hopley IB, Wells PN (2015) Urinary catheters: history, current status, adverse events and research agenda. J Med Eng Technol. 39(8):459-70.

doi: 10.3109/03091902.2015.1085600

Gage H, Avery M, Flannery C, Williams P, Fader M (2017) Community prevalence of long-term urinary catheters use in England. Neurourol Urodyn. 36(2):293-296.

doi: 10.1002/nau.22961

Gage H, Williams P, Avery M, Murphy C, Fader M (2024) Long-term catheter management in the community: a population-based analysis of user characteristics, service utilisation and costs in England. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 25:e13.

doi: 10.1017/S1463423624000021

Garg G, Baghele V, Chawla N, Gogia A, Kakar A (2016) Unusual complication of prolonged indwelling urinary catheter - iatrogenic hypospadias. J Family Med Prim Care. 5(2):493-494.

doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.192335

Gokhan G, Kahraman T, Kemal K, Semih A (2006) Complete tear of ventral penile skin and penile urethra: a rare infective complication of chronic urethral catheterization. Int Urol Nephrol. 38(3-4):613-4.

doi: 10.1007/s11255-006-6674-3

Jahn P, Beutner K, Langer G (2012) Types of indwelling urinary catheters for long-term bladder drainage in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 10(10):CD004997.

doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004997.pub3

Jindal T, Kamal MR, Mandal SN, Karmakar D (2012) Catheter-induced urethral erosion. Urol Nurs. 32(2):100-101

Munien K, Ravichandran K, Flynn H, Shugg N, Flynn D, Chambers J, Desai D (2024) Catheter-associated meatal pressure injuries (CAMPI) in patients with long-term urethral catheters-a cross-sectional study of 200 patients. Transl Androl Urol. 13(1):42-52.

doi: 10.21037/tau-23-445

Public Health England (2016)

English surveillance programme for antimicrobial utilisation and resistance (ESPAUR). Annual Report 2016. Public Health England, London

Reid S, Brocksom J, Hamid R et al (2021) British Association of Urological Surgeons (BAUS) and Nurses (BAUN) consensus document: management of the complications of long-term indwelling catheters. BJU Int. 128(6):667-677.

doi: 10.1111/bju.15406

Shackley DC, Whytock C, Parry G et al (2017) Variation in the prevalence of urinary catheters: a profile of National Health Service patients in England. BMJ Open. 7(6):e013842.

doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013842

Shenhar C, Mansvetov M, Baniel J, Golan S, Aharony S (2020) Catheter-associated meatal pressure injury in hospitalized males. Neurourol Urodyn. 39(5):1456-1463.

doi: 10.1002/nau.24372

Simpson P (2017) Long-term urethral catheterisation: guidelines for community nurses. Br J Nurs. 26(9):S22-S26.

doi: 10.12968/bjon.2017.26.9.S22

Thakkar Y, Saha S, Singhal M, Agarwal A (2022) Iatrogenic hypospadias: a curse of the care. Clin Surg. 7:3567

Tremayne P (2020). Managing complications associated with the use of indwelling urinary catheters. Nurs Stand. 35(11):37-42.

doi: 10.7748/ns.2020.e11599

Yates A (2018) Catheter securing and fixation devices: their role in preventing complications. Br J Nurs. 27(6):290-294.

doi: 10.12968/bjon.2018.27.6.290

Youssef N, Shepherd A, Best C et al (2023) The quality of life of patients living with a urinary catheter and its associated factors: a cross-sectional study in Egypt. Healthcare (Basel). 11(16):2266.

doi: 10.3390/healthcare11162266

Zhao T, Du G, Zhou X (2022) Inappropriate urinary catheterisation: a review of the prevalence, risk factors and measures to reduce incidence. Br J Nurs. 31(9):S4-S13.

doi: 10.12968/bjon.2022.31.9.S4