References

Attolife (2025) Does ketamine appear on drug tests?

https://www.attolife.co.uk/blog/2025/1/does-ketamine-appear-on-drug-tests/ (accessed 2 May 2025)

Belal M, Downey A, Doherty R et al; BAUS Section of Female, Neurological and Urodynamic Urology (2024) British Association of Urological Surgeons Consensus statements on the management of ketamine uropathy. BJU Int. 134(2):148-154. doi: 10.1111/bju.16404

Cancer Research UK (2025) Urostomy (ileal conduit).

https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/bladder-cancer/treatment/invasive/surgery/urostomy-ileal-conduit (accessed 30 April 2025)

Castellani D, Pirola GM, Gubbiotti M et al (2020). What urologists need to know about ketamine-induced uropathy: A systematic review. Neurourol Urodyn. 39(4):1049-1062. doi: 10.1002/nau.24341

Clinical Pathways (2025) Uncomplicated urinary tract infection for women aged 16-64 with suspected UTI.

https://clinicalpathways.uk/pharmacy/uti/ (accessed 30 April 2025)

Cole M, Dasari S (2024) Case Report #41: Ketamine Bladder Pain.

https://fpm.ac.uk/documents/case-report-41-ketamine-bladder-pain-dr-matthew-cole-and-dr-sunil-dasari/management (accessed 30 April 2025)

Drugwise (2024) Ketamine.

https://www.drugwise.org.uk/ketamine/ (accessed 30 April 2025)

Duan Q, Wu T, Yi X, Liu L, Yan J, Lu Z (2017) Changes to the bladder epithelial barrier are associated with ketamine-induced cystitis. Exp Ther Med. 14(4):2757-2762. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.4913

European Association of Urology (2025) Urological infections guideline.

https://uroweb.org/guideline/urological-infections/ (accessed 30 April 2025)

Grilo N, Chartier-Kastler E, Grande P, Crettenand F, Parra J, Phé V (2021) Robot-assisted supratrigonal cystectomy and augmentation cystoplasty with totally intracorporeal reconstruction in neurourological patients: technique description and preliminary results. Eur Urol. 79(6):858-865. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.08.005

Hoffman A, Dolezal KA, Powell R (2025) Dysuria: evaluation and differential diagnosis in adults. Am Fam Physician. 111(1):37-46

Hong YL, Yee CH, Tam YH, Wong JH, Lai PT, Ng CF (2018) Management of complications of ketamine abuse: 10 years' experience in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J. 24(2):175-181. doi: 10.12809/hkmj177086

Hottat A, Hantson P (2023) Toxicity patterns associated with chronic ketamine exposure. Toxicologie Analytique et Clinique 35(2):113-123.

doi: 10.1016/j.toxac.2023.02.001

Jeong SJ, Oh SJ (2020) The current positioning of augmentation enterocystoplasty in the treatment for neurogenic bladder. Int Neurourol J. 24(3):200-210. doi: 10.5213/inj.2040120.060

Jhang JF, Hsu YH, Kuo HC (2015) Possible pathophysiology of ketamine-related cystitis and associated treatment strategies. Int J Urol. 22(9):816-25. doi: 10.1111/iju.12841

Jhang JF, Birder LA, Kuo HC (2023) Pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and management of ketamine-induced cystitis. Tzu Chi Med J. 35(3):205-212. doi: 10.4103/tcmj.tcmj_94_23

Li CC, Wu ST, Cha TL, Sun GH, Yu DS, Meng E (2019) A survey for ketamine abuse and its relation to the lower urinary tract symptoms in Taiwan. Sci Rep. 9(1):7240. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43746-x

Lin JW, Lin YC, Liu JM et al (2022) Norketamine, the main metabolite of ketamine, induces mitochondria-dependent and ER stress-triggered apoptotic death in urothelial cells via a Ca2+-regulated ERK1/2-activating pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 23(9):4666. doi: 10.3390/ijms23094666

Lindsay J, Wood D (2020) Ketamine uropathy, an update.

https://www.urologynews.uk.com/features/features/post/ketamine-uropathy-an-update (accessed 30 April 2025)

Misra S (2018) Ketamine-associated bladder dysfunction—a review of the literature. Curr Bladder Dysfunct Rep. 13:145-152. doi: 10.1007/s11884-018-0476-1

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2018) Urinary tract infection (lower): antimicrobial prescribing. NICE guideline [NG109].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng109 (accessed 30 April 2025)

Ng CF, Chiu PK, Li ML et al (2013) Clinical outcomes of augmentation cystoplasty in patients suffering from ketamine-related bladder contractures. Int Urol Nephrol. 45(5):1245-51. doi: 10.1007/s11255-013-0501-4

Niesters M, Martini C, Dahan A (2014) Ketamine for chronic pain: risks and benefits. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 77(2):357-67. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12094

Office for National Statistics (2024) Drug misuse in England and Wales: year ending March 2024.

https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/articles/drugmisuseinenglandandwales/yearendingmarch2024 (accessed 30 April 2025)

Orhurhu VJ, Vashisht R, Claus LE, Cohen SP (2023) Ketamine toxicity.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541087/ (accessed 30 April 2025)

Ou YL, Liu CY, Cha TL, Wu ST, Tsao CW (2018) Complete reversal of the clinical symptoms and image morphology of ketamine cystitis after intravesical hyaluronic acid instillation: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 97(28):e11500. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011500

Peltoniemi MA, Hagelberg NM, Olkkola KT, Saari TI (2016) Ketamine: a review of clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in anesthesia and pain therapy. Clin Pharmacokinet. 55(9):1059-77. doi: 10.1007/s40262-016-0383-6

Shahani R, Streutker C, Dickson B, Stewart RJ (2007) Ketamine-associated ulcerative cystitis: a new clinical entity. Urology. 69(5):810-2. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.01.038

Stonehouse R (2024) Ketamine bladder: Special clinics as youth addiction 'explodes'.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-bristol-68826392 (accessed 30 April 2025)

Vetterlein MW, Buhné MJ, Yu H et al (2022) Urinary diversion with or without concomitant cystectomy for benign conditions: a comparative morbidity assessment according to the updated European Association of Urology guidelines on reporting and grading of complications. Eur Urol Focus. 8(6):1831-1839. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2022.02.008

Vizgan G, Huamán M, Rychik K, Edeson M, Blaivas JG (2023) Ketamine-induced uropathy: A narrative systemic review of surgical outcomes of reconstructive surgery. BJUI Compass. 4(4):377-384. doi: 10.1002/bco2.239

Winstock AR, Mitcheson L, Gillatt DA, Cottrell AM (2012) The prevalence and natural history of urinary symptoms among recreational ketamine users. BJU Int. 110(11):1762-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11028.x

Wu P, Wang Q, Huang Z, Wang J, Wu Q, Lin T (2016) Clinical staging of ketamine-associated urinary dysfunction: a strategy for assessment and treatment. World J Urol. 34(9):1329-36. doi: 10.1007/s00345-016-1759-9

Zeng J, Lai H, Zheng D et al (2017) Effective treatment of ketamine-associated cystitis with botulinum toxin type A injection combined with bladder hydrodistention. J Int Med Res. 45(2):792-797. doi: 10.1177/0300060517693956

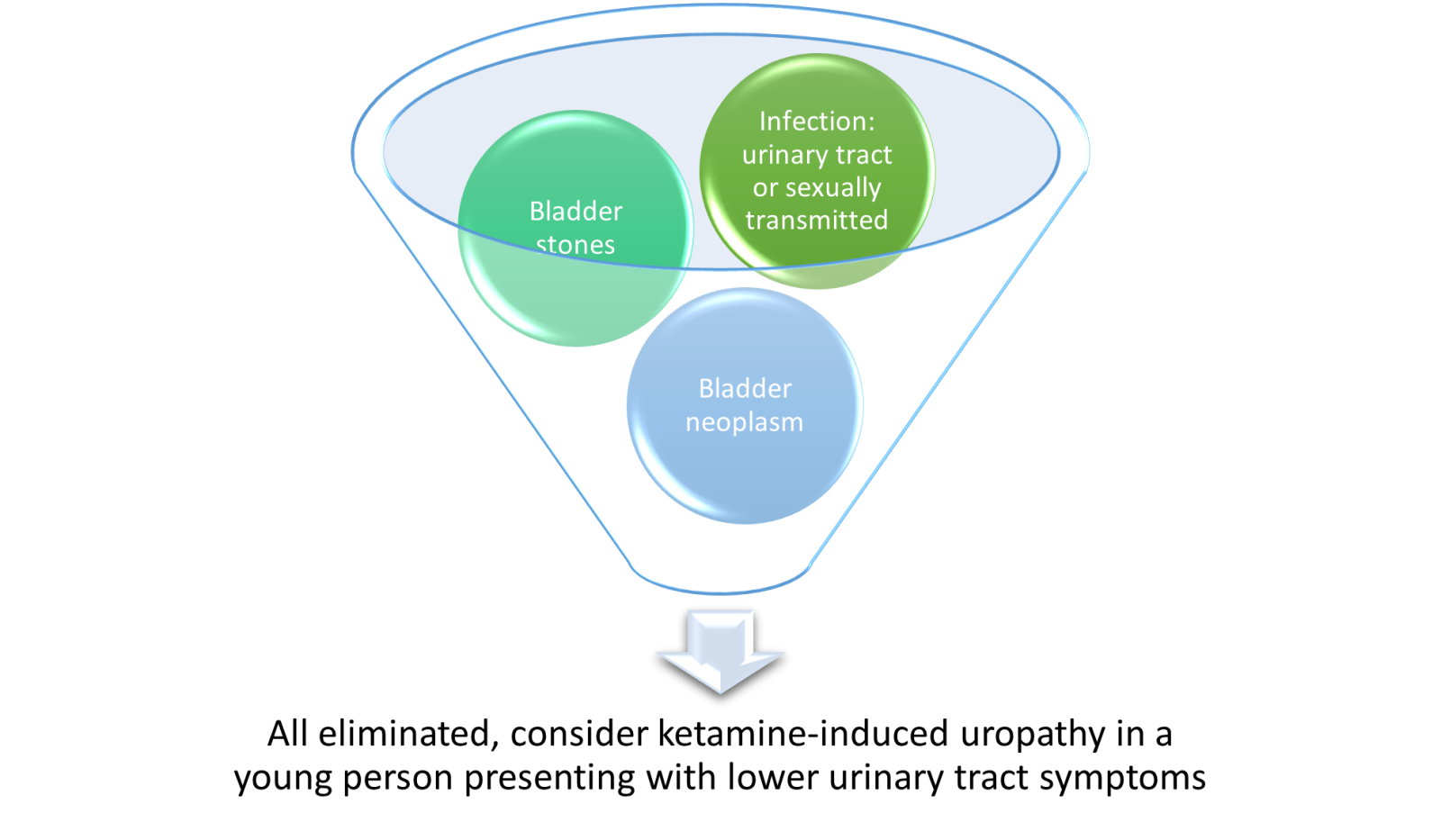

If ketamine-induced uropathy is suspected or if the person is unresponsive to treatment, they should be referred to urology. The urgency of referral will be based on clinical symptoms.

If ketamine-induced uropathy is suspected or if the person is unresponsive to treatment, they should be referred to urology. The urgency of referral will be based on clinical symptoms.

The most important action is to support the person to stop using ketamine – 51% of people experience an improvement of symptoms when they stop using ketamine (Castellani et al, 2020).

The most important action is to support the person to stop using ketamine – 51% of people experience an improvement of symptoms when they stop using ketamine (Castellani et al, 2020).