How do I get started?

You don’t need to be an expert in QI to undertake a QI project, and it doesn’t need to be big or complex (The Health Foundation, 2021). Small improvements can have a significant impact on patients, but to be successful you will need to know about improvement methodology, so your approach is both a systematic and continuous process (The Health Foundation 2021). Backhouse and Ogunlayi (2020) indicated that successful improvement comprises 20% technical and 80% human skill.

Some key skills you will need include:

- Good project and time management

- Ability to collaborate with stakeholders and all participants

- Good communication skills

- Good understanding of improvement methodology

- Ability to understand the data that you will capture to measure the impact of your improvement intervention

(Jones, 2019).

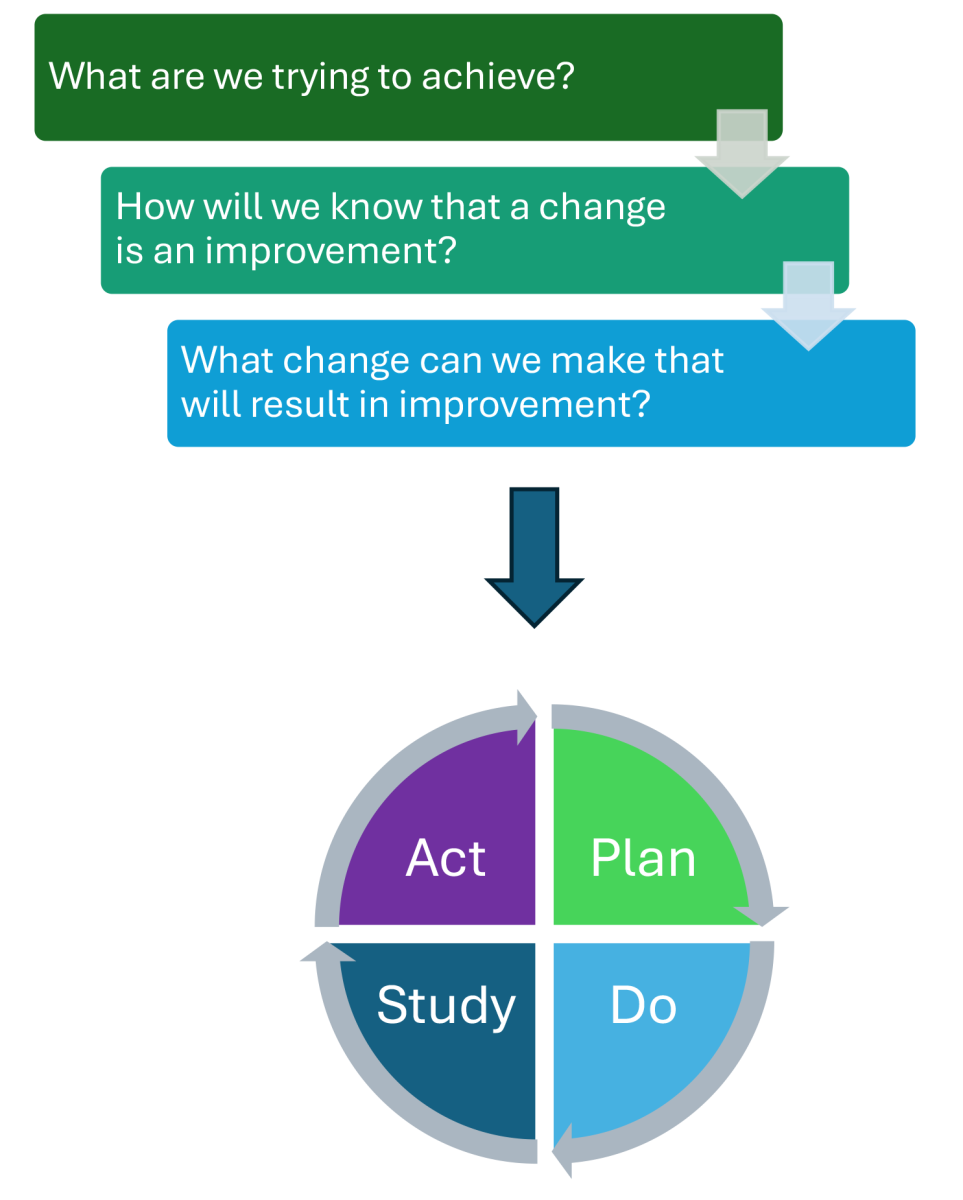

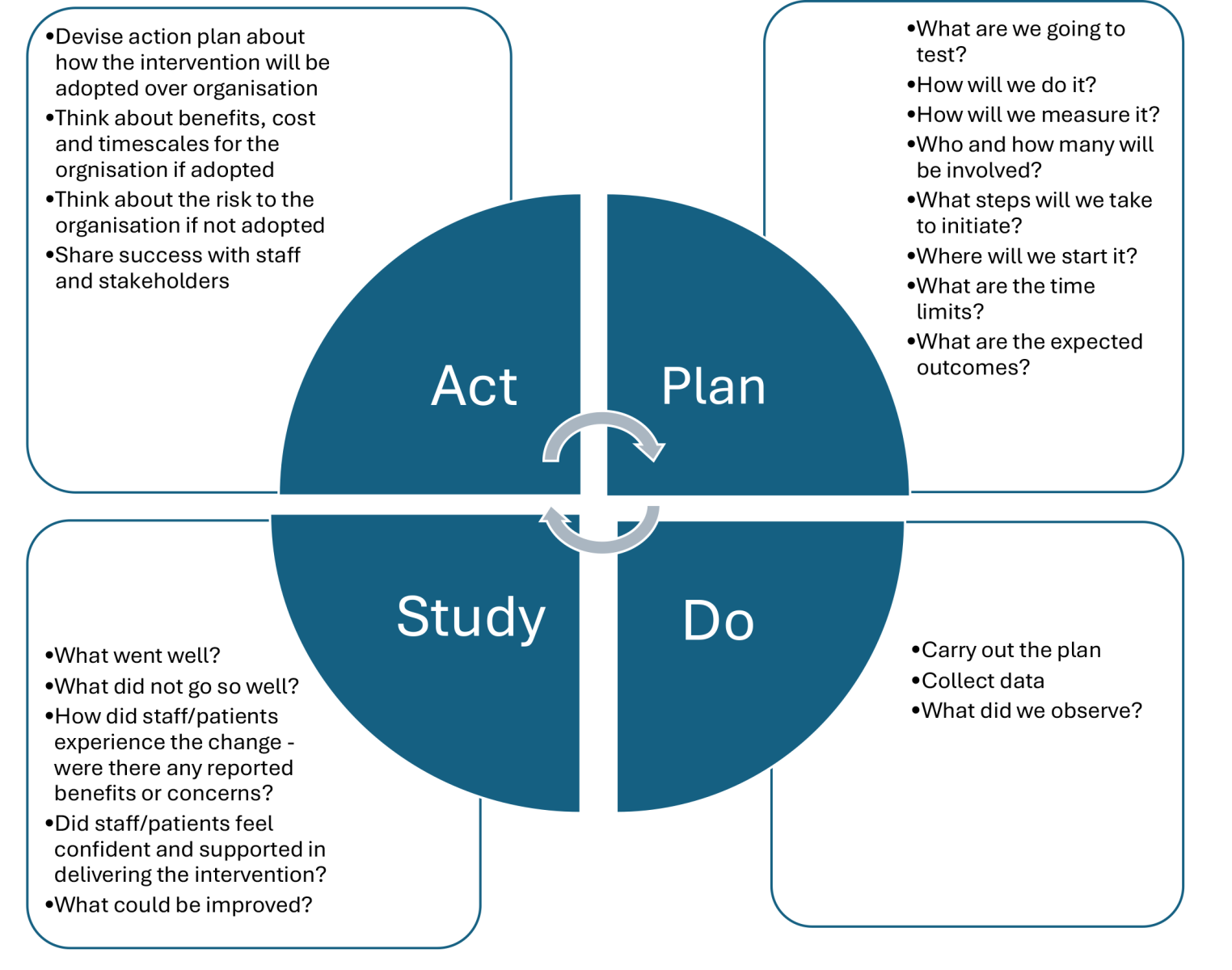

There are a number of established improvement frameworks available to guide QI projects (The Health Foundation, 2021). One widely used within NHS organisations is the Model for Improvement (Improvement Cymru Academy, 2024). This straightforward approach encourages starting on a small scale, making the work less disruptive to practice while supporting continuous change (The Health Foundation, 2021). It uses short, structured cycles of testing, known as plan–do–study–act (PDSA) cycles (Figure 2), in which potential improvements are trialled, reviewed, and refined. Each cycle offers an opportunity to gather insights and learn from outcomes in a structured and continuous way (Improvement Cymru Academy, 2024). Each PDSA cycle is linked to three key questions which need to be considered throughout your QI project:

- What are we trying to accomplish?

- How will we know that a change is an improvement?

- What change can we make that will result in improvement?

(Improvement Cymru Academy, 2024)

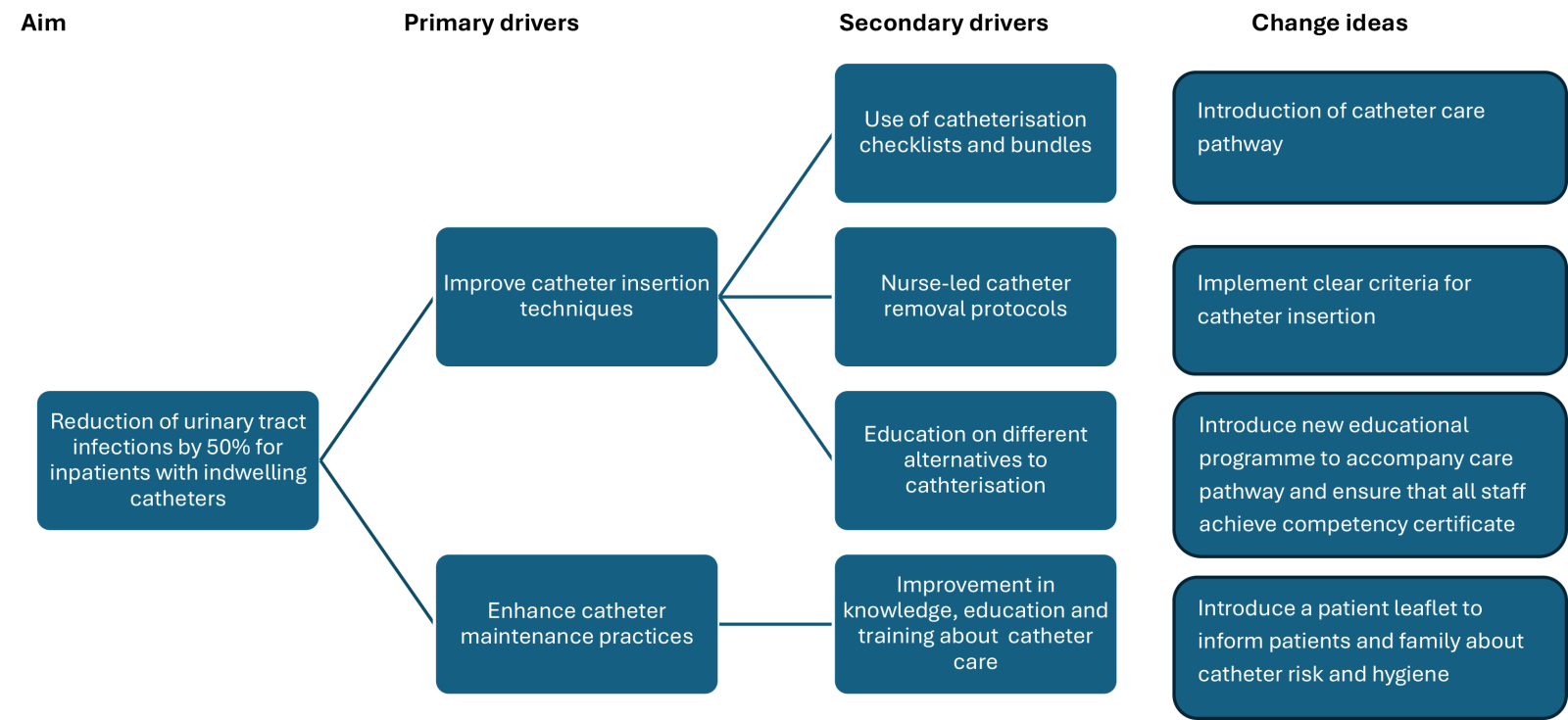

Understanding the problem

The first stage of any improvement project is to clearly define the problem and use data to identify gaps in current performance and practice, as well as the underlying causes (The Health Foundation, 2021). This can involve drawing on various types of information and data which will also give a clear baseline to assess the impact of your improvement project both during and following implementation (NHS England and NHS Improvement, 2023b). Data can include quantitative data, qualitative data or a mixture of both.