Protecting the urethra

Looking at the anatomy and physiology of the urethra, it is clear how important its integrity is to patient safety and comfort. Many catheter users would say that the most important role of the urethra is in protecting against the development of urinary tract infections (UTIs) - these are often reported by patients as being the most troublesome and painful condition linked to catheterisation.

As well as reducing the chance of developing a UTI, taking steps to reduce the likelihood of damaging the lining of the urethra while catheterising can have a number of clinical benefits for the patient:

- Using catheters that have integral hydrophilic properties or a coating to make them easier to both insert and remove can help to keep the urethral lining intact. This makes it harder for bacteria to breach the protective barrier and cause infection, decrease the risk of developing UTIs.

- Ex-vivo research found that a catheter with integral hydrophilic properties needed less force to insert and remove it than catheters that use hydrophilic coatings (Burns et al, 2025).

- This study also found that catheters that use hydrophilic coatings left some of the coating within the urethra after they had been removed while the catheter with integral hydrophilic properties left no residue.

- Burns et al (2025) looked for evidence of microtrauma to the urethral lining following removal of the catheters. While all intermittent catheters studied caused some degree of damage to the urethral lining, the hydrophilic coated catheters caused more damage to the uroepithelial membrane than the catheter with integral hydrophilic properties or the uncoated catheter.

- In a previous study, Burns et al (2024) showed that the surface of coated catheters can dry out while in the urethra and then stick to the lining of the urethra. This can mean that more force is needed to remove the catheter and can damage the urethral lining when the catheter is pulled away from it. In contrast, the catheter with integral hydrophilic properties needed less force to begin removing it, which suggests that a coating-free hydrophilic surface could reduce the risk of urethral microtrauma.

- If the lining of the urethra is injured, the scar tissue that develops in response can make it harder to catheterise as this narrows the diameter of the urethra.

- A breach in the urethral lining will also disrupt the mucous membrane, which may increase the pain experienced during or after catheterising as urine comes into direct contact with the epithelial cells.

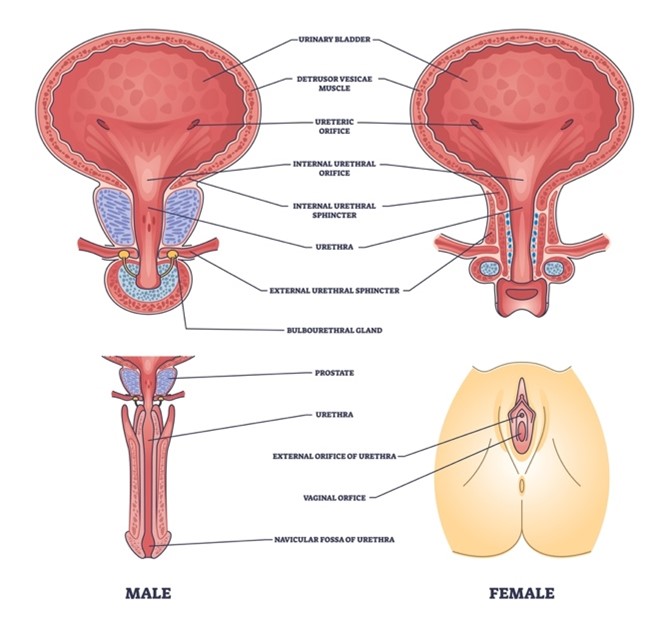

- The muscles in the urethra form the sphincters which control release of urine. If these contract, it can make insertion and removal of the catheter harder.

- The psychological effects of fearing pain on insertion and/or removal, and worry about contracting further UTIs are very real for catheter users. These can also have physical effects as they can lead the user to tense up inadvertently before inserting/removing the catheter, which can make the process harder.

Conclusions

Whether you are prescribing a catheter to someone for the first time, or reviewing the practice of an experienced user, take a moment to make sure that the solution that you are providing isn’t inadvertently causing unnecessary damage. This will ensure that you are providing the best possible care for all those who use intermittent self-catheterisation