References

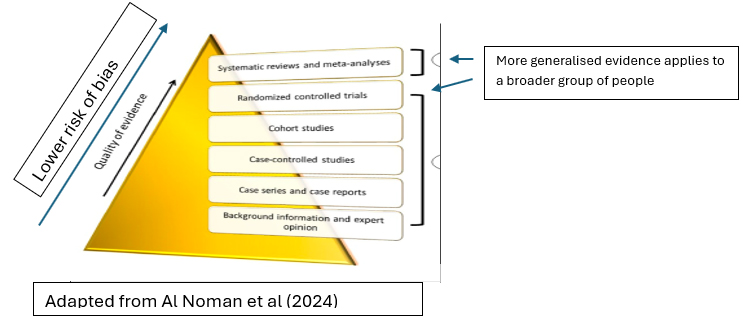

Al Noman A, Sarkar O, Mohsin Mita T, Siddika K, Afrose F (2024) Simplifying the concept of level of evidence in lay language for all aspects of learners: In brief review. Intelligent Pharmacy. 2:270-273. doi: 10.1016/j.ipha.2023.11.002

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S et al; Medical Research Council Guidance (2008) Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 337:a1655. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1655

Dechartres A, Trinquart L, Atal I et al (2017) Evolution of poor reporting and inadequate methods over time in 20 920 randomised controlled trials included in Cochrane reviews: research on research study. BMJ. 357:j2490. doi:10.1136/bmj.j2490

Ellis P (2016) Understanding Research for Nursing Students. 3

rd edn. Sage Publications Ltd, London

Ellis P (2024a) Evidence based practice.

Wounds UK 20(3):76-79

Ellis P (2024b) Evidence based practice 2: hierarchies and barriers.

Wounds UK 20(4):82-84

Kredo T, Bernhardsson S, Machingaidze S et al (2016) Guide to clinical practice guidelines: the current state of play. Int J Qual Health Care. 28(1):122-8. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzv115

Kumah EA, McSherry R, Bettany-Saltikov J, van Schaik P (2022) Evidence-informed practice: simplifying and applying the concept for nursing students and academics. Br J Nurs. 31(6):322-330. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2022.31.6.322

Lima JP, Mirza RD, Guyatt GH (2023) How to recognize a trustworthy clinical practice guideline. J Anesth Analg Crit Care. 3(1):9. doi: 10.1186/s44158-023-00094-7

Mahoney K (2025) An introduction to evidence-based practice.

https://www.clp-hub.com/personal-development/evidence-based-practice (accessed 23 April 2025)

McSherry R, Artley A, Holloran J (2006) Research awareness: an important factor for evidence-based practice?. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 3(3):103-115.

doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2006.00059.x

Moule P (2021) Making Sense of Research in Nursing and Health and Social Care. 7th edn. Sage, London

Murad MH, Asi N, Alsawas M, Alahdab F (2016) New evidence pyramid. Evid Based Med. 21(4):125-127. doi: 10.1136/ebmed-2016-110401

Nursing and Midwifery Council (2018) The code: professional standards of practice and behaviour for nurses, midwives and nursing associates. https://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/code/ (accessed 16 April 2025)

Paquette M, Kelecevic J, Schwartz L, Nieuwlaat R (2019) Ethical issues in competing clinical trials. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 14:100352. doi: 10.1016/j.conctc.2019.100352

Ponce OJ, Alvarez-Villalobos N, Shah R et al (2017). What does expert opinion in guidelines mean? a meta-epidemiological study. Evid Based Med. 22(5):164-169. doi: 10.1136/ebmed-2017-110798

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D; CONSORT Group (2010) CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 340:c332. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c332

Ubbink DT, Guyatt GH, Vermeulen H (2013) Framework of policy recommendations for implementation of evidence-based practice: a systematic scoping review. BMJ Open. 3(1):e001881. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001881

World Medical Association (2013) Declaration of Helsinki: Medical Research Involving Human Participants.

https://www.wma.net/what-we-do/medical-ethics/declaration-of-helsinki/ (accessed 23 April 2025)